By Justin P. Forkner 1

Indiana, like most other states, faces a critical shortage of attorneys. And like most states, Indiana’s attorney shortage is complicated. It defies a single solution because it isn’t a single problem—in fact, just to call it an “attorney” shortage misses the mark—it is a legal professional shortage. And this shortage adversely affects access to justice, economic and workforce development, and the civic health of our communities.

Yet the potential solutions are just as myriad as the problems. The answer is not simply “more lawyers” but instead a complete reevaluation of how legal services are provided. It is rethinking who can provide those services and reimagining how we get individuals to provide them in areas and fields where they aren’t today. To that end, on April 4, 2024, the Indiana Supreme Court created the Commission on Indiana’s Legal Future, tasking it to explore the problem from all angles and make recommendations to the Court on ways to address it. 2

Though “more lawyers” aren’t the panacea, this would certainly help. 3 And when I present on the dearth of attorneys in Indiana, I often describe it as the confluence of three rivers, or problems: 4 the age of our attorneys; where those attorneys are located; and our attorney production line. While other efforts through the Commission will aim to address where our attorneys are and how to encourage younger lawyers to practice where they aren’t, this article highlights a route Indiana traversed in the years before the Commission was created; a route aimed at addressing the last element of our three rivers problem—the attorney production line.

Rivers One and Two

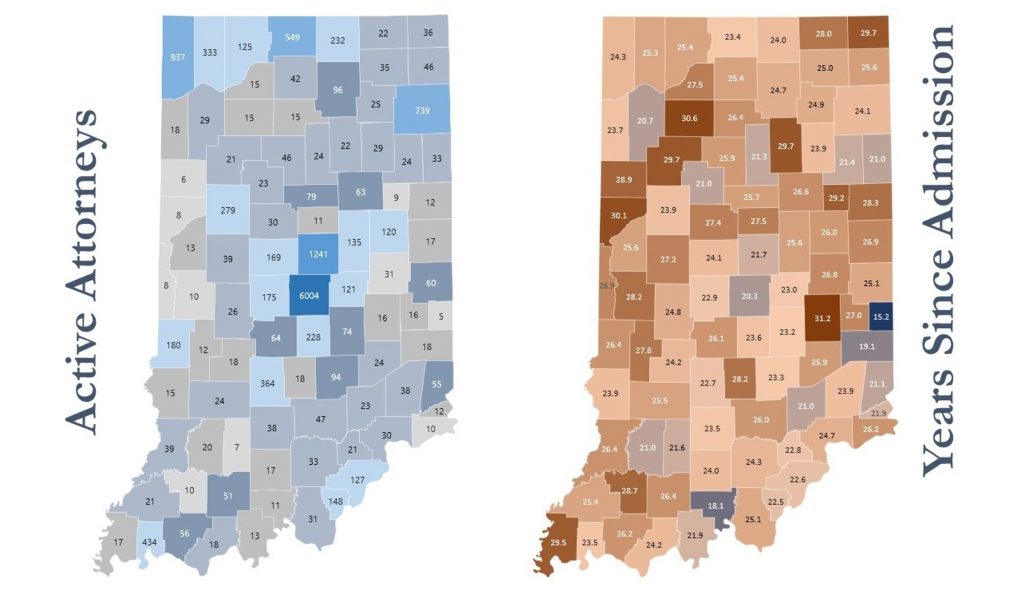

To understand the impact of Indiana’s attorney production line, it is helpful to first see the first two problems and how they merge. In short, where we have fewer attorneys in our state, those attorneys trend older. And that’s most evident in our rural counties, where lawyers are retiring with fewer younger lawyers coming in to replace them.

Attorney Age

To track an attorney’s “age,” we use their date of admission to the bar as a proxy. 5 While some attorneys, like myself, come to the law as a second career, the majority attend law school directly after college. So we can approximate that a newly admitted lawyer is about 25 years old, making an attorney 15 years past admission roughly 40 years old and so on. From that, we know that the average retirement “age” of an Indiana attorney is 39 years past admission, or roughly 64 years old.

The average “age” of an Indiana lawyer is 22.4 years past admission, meaning the average age of an Indiana attorney is roughly 47 years old. Though this doesn’t sound too bad, it becomes a challenge when you localize it. The average is much higher, 25.7 years, for lawyers in our non-Metropolitan Statistical Areas than it is in our most populous ten counties, 23.3 years, and in our largest county, 20.3 years. 6 These numbers lead to the second problem.

Attorney Locations

To determine where Indiana’s attorneys are located, we use their registered business address. 7 Including judicial officers, there are roughly 19,000 active attorneys in Indiana. 8 When you reduce that number by lawyers who maintain active licenses but are based out of state, we are closer to 16,000 attorneys actively practicing law within our state.

But those lawyers are predominantly clustered in our state’s urban areas; over half of them are in Marion County, where Indianapolis is located, and the surrounding 7 donut counties. 9 Thus, some of Indiana’s 92 counties have as few as a 6 active attorneys—and when you reduce that number by the judge(s) and prosecutor(s), many counties have only one or two lawyers representing its residents, businesses, and governmental entities.

River Three

To be sure, these first two problems are not unique to lawyers in Indiana. Medical providers, mental health professionals, veterinarians, accountants, and others are all in scarcer supply in our rural counties. But what is unique to lawyers in Indiana is a recent reduction in legal educational offerings.

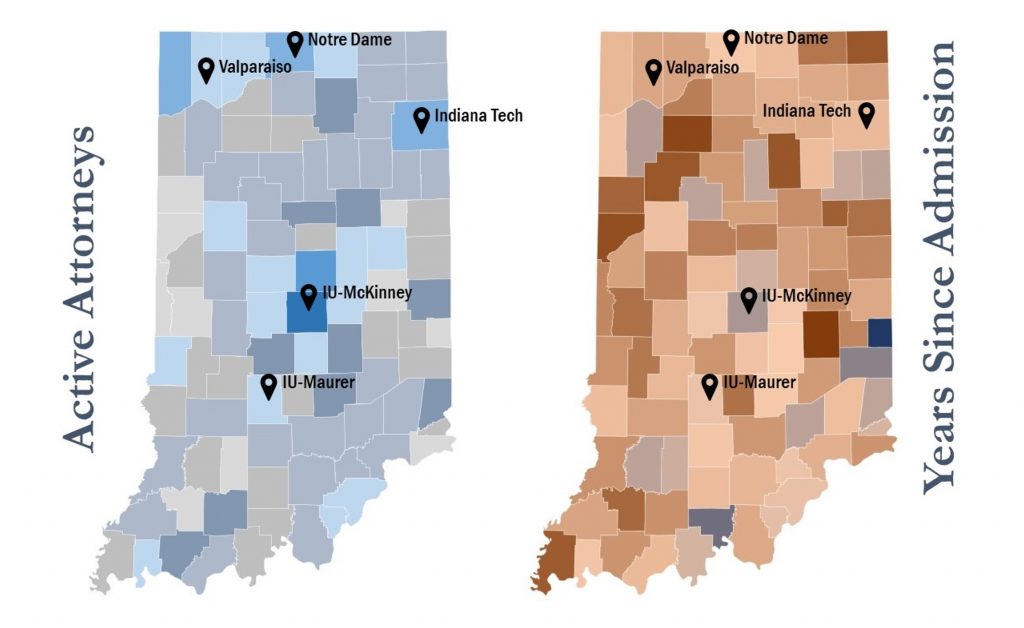

In 2017, we had five law schools: Indiana University’s Robert H. McKinney School of Law in Indianapolis and Maurer School of Law in Bloomington; Valparaiso Law School in northwestern Indiana’s Porter County; Notre Dame Law School in South Bend; and Indiana Tech Law School in Fort Wayne. But in a three-year stretch, two of those schools closed: Indiana Tech in 2017; and Valparaiso in 2020.

Indiana Tech’s closure had a small impact on attorney output—it was relatively new and had not begun producing large numbers of graduates. But Valparaiso’s closure had a much larger impact, as it accounted for about 18% of Indiana’s bar exam applicants, recruited heavily from Indiana residents, and produced an outsized percentage of public service lawyers.

By contrast, Notre Dame has roughly 180 students in each graduating class, but only a handful are Indiana residents and only about 8% take Indiana’s July bar exam. IU Maurer graduates around 170 students each year with roughly half of them being Indiana residents, but only around 38% of those graduates sit for the exam. As for IU McKinney, the graduating class is generally around 225–245 students with roughly 80% of those students being Indiana residents and 74% sitting for the exam. 10 So while Indiana has three law schools, only IU McKinney predominantly enrolls Indiana residents and sees the majority of its graduates take the Indiana bar exam. It is also the only law school to offer an evening program as well as the only law school with a hybrid online program. Yet both of those programs still require in-person, on-campus work. And both programs cost the same per credit hour as the traditional daytime program.

The closure of two of our law schools and the above statistics leads to the confluence of Indiana’s three problems: the areas of our state with fewer and older active lawyers not only suffer from an access-to-justice problem, but the people in those counties who might become lawyers have an access-to-law-school problem. With that third river drying up, these areas aren’t just legal deserts, they’re law school deserts.

And that’s a significant hurdle to overcome when we know that a substantial driver of practicing in a rural part of our state is a preexisting connection to that area—a family, a career, a community. Would-be lawyers from these areas must either uproot, move, and leave their jobs or undergo grueling commutes back and forth to school. 11 And this is a problem not shared by other professions like doctors, nurses, accountants, and veterinarians. For those fields, Indiana has far more extensive education networks. 12

Given the challenges of getting individuals in large parts of our state to law school, the question then becomes, “Can we bring law school to them?”

The Purdue Proposal

Into Indiana’s law school desert problem stepped Purdue University and Concord Law School. 13 Concord is a fully online law school that was founded in 1998 as part of Kaplan University and acquired in 2018 by Purdue—Indiana’s land-grant university—as part of its Purdue Global system. Concord costs roughly $50,000 in total for its four-year program. Though the law school is not accredited by the ABA, it is accredited by the State of California. 14 A Concord student is, typically, not a “traditional” law student. As of 2022, Concord’s student body was sixty percent non-white, over fifty percent female, had a median age of forty-three, tended to work full-time and live outside the commute range of brick-and-mortar schools, and nearly twenty percent were directly linked to military service as a veteran or as the immediate family member of an active-duty servicemember.

In spring 2022, Purdue proposed amendments to our Admission and Discipline rules that would allow graduates of non-ABA accredited law schools to sit for the Indiana bar exam. The law school, however, would have to have been accredited by one or more state, regional, or national bodies that specifically accredit law schools and be operated by or affiliated with a state educational institution whose legal education program or degree was approved by the Indiana Commission for Higher Education. In practical terms, the proposal applied only to Concord Law School by virtue of its California accreditation and affiliation with Purdue.

Working Group

To examine Purdue’s proposal, the Indiana Supreme Court assembled a working group. The working group was chaired by one of our intermediate appellate court judges and included a mix of practitioners, trial court judges, rural community representatives, educators, and bar examiners. It met six times over six months and received briefings from a cross-section of presenters, including California’s Bar Accreditation staff, the ABA’s Accreditation Committee, Concord Law and Purdue Global staff, young lawyers, and current law students.

The working group then issued a report, identifying advantages and challenges to the idea of allowing Concord graduates to sit for the Indiana bar exam. The report recognized that remote learning was a COVID necessity that had become a post-COVID reality and that Concord could provide quality, affordable access to a legal education for folks in our law school deserts. 15 But the report also expressed doubt that Concord, alone, could solve our lawyer shortage and lawyer diversity challenges. It feared that Concord graduates may generate more character and fitness issues than the state’s other law school graduates and that allowing Concord graduates to take the exam might depress our state’s bar passage rates. 16 And there was a significant concern that the Indiana-centric nature of the proposal might run afoul of the U.S. Constitution’s Dormant Commerce Clause. 17

And so, instead of making a direct recommendation to adopt or reject Purdue’s proposal, the report provided the Court with a list of recommendations that the working group felt should be preconditions to approval. These included mandating certain ABA-style reporting requirements, enforcing a higher bar passage rate for Concord graduates, limiting class sizes, and obligating Purdue to target marketing and job placement efforts in rural legal deserts. The Court sought public comment on the proposal and report. 18

Public Response & Comments

The comments we received were mixed. By and large, the institutional responses were not favorable. The Indiana State Bar Association (ISBA) believed our state first needed an independent accrediting agency to ensure a non-ABA accredited law school’s standards met the level of practice expected of Indiana lawyers. 19 The Indianapolis Bar Association (Indy Bar), our largest local bar association, feared that the impact on Indiana’s lawyer shortage would be minimal; waiving ABA standards would diminish the quality of the practice of law; and without in-person instruction in some form, new lawyers would suffer from lack of access to mentorship and practical skills-building. 20 The two Indiana University law schools expressed similar concerns, and they also pointed to Concord’s higher drop-out rate—roughly 50%. 21 On the other hand, Indiana Legal Services (ILS), our largest legal aid organization, was in favor of the proposal.

At the individual level, attorney responses broke into two basic camps. Those who opposed the proposal focused heavily on the benefits of face-to-face peer interaction in law school and the challenge of developing, in a fully online environment, the soft skills and networking necessary for effective legal practice. Those who supported the proposal largely expressed a view that Indiana needed lawyers, and if the Concord Law School graduates could pass the bar exam and meet the other qualifications for admission, then it shouldn’t matter where they earned their degree. 22 Members of the public also generally commented in favor of the proposal. 23 And so, the Court had a decision to make.

The New Way Forward

At the time Purdue submitted its proposal, Indiana was one of only nineteen states that limited eligibility to take the bar exam, under any circumstances, to graduates of ABA-approved law schools. 24 But it was clear from the institutional, professional, and public response that while there was support for shifting away from that position as a result of the state’s attorney shortage, the initial proposal was not the best solution to our law school desert problem. The perceived risks outweighed the potential benefits.

So, in November 2023, after considering all the feedback and doing additional analysis, the Indiana Supreme Court posted for comment a new, broader proposal to amend its Admission & Discipline Rules that provided a process by which otherwise-qualified individuals, who did not graduate with a law degree from an ABA-accredited law school, could sit for our bar exam.

This new proposal included a mechanism for two sets of individuals to seek a waiver of the ABA accreditation requirement:

- A graduate of a non-ABA accredited U.S. law school who was eligible upon graduation to take the bar exam of another state; and

- A graduate of a non-U.S. law school who subsequently completed a graduate degree in American law from an ABA-accredited law school.

In both instances, Indiana’s Board of Law Examiners would be given authority to recommend that the individual sit for the bar exam based on their education and experience, but the Court would make the ultimate determination. 25 And in both instances, the individual would be subject to the same admissions requirements as graduates from an ABA-accredited law school. 26

The response to this proposal was, overall, favorable. The ISBA was supportive. IndyBar was not opposed but urged the Court to proceed with caution. 27 As for the IU law schools, they were still not in favor of allowing graduates of non-ABA accredited U.S. law schools to take the bar exam, 28 but they did not oppose allowing graduates of foreign law schools with graduate degrees in American law to take the exam. 29 ILS was again in favor but suggested concrete standards to frame the Board’s discretion. And comments from individual practitioners and members of the public were again split, but generally more favorable than not. 30

As a result, on February 14, 2024, the Court approved a modified version of the new proposal, incorporating language that the Board of Law Examiners “should grant a waiver when doing so would be in the public interest after balancing all relevant factors including the applicant’s educational history and achievement, work history and achievement, bar exam results from other jurisdictions, desire to practice law in Indiana, and familiarity with the American legal system.” 31 This new rule goes into effect July 1, 2024, meaning the first eligible applicants would be seeking a waiver to sit for the February 2025 exam. 32

Conclusion

If you take one thing away from this article it is that the attorney shortage, in Indiana and across the United States, is complicated. It is fueled by any number of factors, some preventable, some unavoidable, and some inevitable. And there is no one single solution or standard set of solutions that will work everywhere.

Instead, there are any number of avenues to explore, each of which will come with its own unique challenges and sources of both resistance and acceptance. But, as a legal profession, we cannot remain complacent. We must instead commit our energy to fully understanding the risks and benefits of these new ideas; we cannot simply cast off one as too small or write off another as too large. Any one of them, applied effectively based on a state’s needs, could target a discrete aspect of the shortage as part of a collective solution. And we must come to grips with the idea that, in many ways, “the way we’ve always done it” got us to this point and will not get us out. “Do nothing” is not the answer.

End Notes

1 This article would not have been possible without the inestimable assistance of many people engaged in Indiana’s online law school endeavor. I hope the article reflects the tremendous effort they invested. And I owe my highest personal thanks to three tremendous players in the field of Indiana’s legal education reform: Josh Woodward, Counsel to the Chief Justice of Indiana; Brad Skolnik, Executive Director of the Indiana Supreme Court’s Office of Admission and Continuing Education; and the Honorable Nancy H. Vaidik, Judge of the Indiana Court of Appeals, chair of the Indiana Supreme Court’s Purdue University Global Concord Law School Working Group, and co-chair of the Indiana Supreme Court’s Commission on Indiana’s Legal Future.

2 https://www.in.gov/courts/files/order-other-2024-24S-MS-116.pdf

3 The ABA’s national average of attorneys per capita is commonly used as a benchmark for where states rank in terms of their attorney population, with a national average of four attorneys per one thousand residents. Indiana sits at 2.3/1000 statewide. This puts us technically in the bottom nine states, although those nine states represent a three-way tie at 2.3/1000, a three-way tie at 2.2/1000, and a three-way tie at 2.1/1000. https://www.abalegalprofile.com/demographics.html. Only one of Indiana’s 92 counties, Marion County, exceeds 4.0/1000. Fifty-two counties are below 1/1000.

4 I would be remiss if I did not thank the source of this analogy, John R. Hammond, III. John is an exceptional lawyer with extensive experience in the legislative arena. He once described a particular legislative session to me as a “Pittsburgh Session,” because the session was occurring at the “confluence of three rivers” of different political dynamics. (Indiana has its own “three rivers” city, of course. Fort Wayne, Indiana, prides itself on sitting at the confluence of the Saint Mary’s, Saint Joseph, and Maumee River.)

5 Our Roll of Attorneys database has an entry for date of birth, but it’s an optional field during our annual registration. Enough attorneys opt out of providing their date of birth that we do not use it as a statistically valid measure.

6 “Metropolitan Statistical Area refers to a federally delineated geographic entity—a county or collection of counties—that are economically tied together around at least one urbanized area. So some Indiana counties that might, on their own, be seen as very rural—like some counties in southeastern Indiana—are considered part of the MSAs centered around urbanized areas in other states like Cincinnati and Louisville.

7 Indiana’s Roll of Attorneys also tracks home addresses, but many lawyers commute from the suburbs to the urban parts of the state where the law firms and government offices are located. Using business address gives a slightly more precise way to track where attorneys practice, although with statewide electronic filing, a lawyer’s footprint can be much larger.

8 Indiana has three broad categories of attorney licensing status: active, inactive, and retired. Ind. Admission & Discipline R. 2.

9 This attorney location disparity then makes the attorney age disparity even more stark. Because a county’s average attorney age isn’t weighted or scaled by the county’s overall population, the gap between the statewide average of 22.4 years and average ages in rural areas like Posey County (29.5 years), Steuben County (29.7 years) or Wabash County (29.7 years) understates the problem. The younger lawyers that bring that statewide average down aren’t in those smaller counties. In Wabash County, for example, over half of the attorneys are in the retirement window; in Marion County, fewer than one-third are.

10 Another 50-100 out-of-state applicants sit for the Indiana bar in July. These numbers also do not account for the bar passage rate. On average, the overall passage rate for the July exam is roughly 70%. Indiana also offers the bar exam in February, but far fewer individuals sit for that test. In February 2024, for example, only 182 individuals sat for the bar exam, including 107 individuals who had previously failed the exam. And, like everywhere else, the February passage rate is significantly lower. The overall passage rate for Indiana’s February 2024 exam was only 41%.

11 Maurer and McKinney both have Rural Justice Initiatives, which are summer externship programs aimed at placing law students with judges in rural counties. Those programs are very well-run and exceedingly popular for both students and judges, but post-graduation placement rates in those counties aren’t high. The same has been the case for other initiatives aimed at placing young law school graduates in rural areas. By and large, unless they’re from there, they’re not going there right after graduation.

12 For example, Indiana has nine medical schools around the state. There are four schools that offer veterinary programs, including one with multiple sites.

13 In 2022, the institution was called Concord Law School. It has since been renamed Purdue Global Law School.

14 Concord complied with about eighty percent of the fifty-four ABA Standards for Approval of Law Schools. Most obviously, Concord does not comply with ABA Standard 311(e), which limits the amount of distance education that may be offered in a J.D. program. ABA Standards 403(a) and 405 relate to the number and tenure status of full-time faculty members; Concord was in the process of hiring sufficient full-time faculty members, but it does not offer a tenure system. Similarly, ABA Standard 603 requires a tenured law library director; as a fully online school, Concord instead offers its students full access to a variety of online legal research databases.

There were also several technical standards which Concord did not meet. ABA Standard 501(b) and its Interpretation 501-3 created a presumption that a school with a non-transfer attrition rate over twenty percent was not in compliance with the obligation to “only admit applicants who appear capable of satisfactorily completing its program of legal education and being admitted to the bar.” Concord’s attrition rate was much higher than twenty percent, and it did not anticipate reaching that number based on its student body looking less like a traditional law school admitted class. And Standards 503 and 509 require law schools to validate any admissions test other than the LSAT and provide certain required disclosures related to the academic program, costs, admitted class composition, student body, graduation rates, employment rates, and bar passage rates. Concord used its own predictive admissions test and annually publishes similar data to the 509 obligations but in a format mandated by California rather than the ABA.

Also, Concord did not—but could—comply with ABA Standard 303(c), which requires education on bias, cross-cultural competency, and racism “at the start” of a law school’s program of instruction and at least one more time prior to graduation; Concord provides this instruction three times over its four-year curriculum, but the first time is in the second year. Concord also did not comply with ABA Standard 311(d), which prohibits awarding J.D. credit for work in a pre-admission program. Instead, to improve success of its more diverse students, Concord was launching a one-credit pre-admission program to train on first-year law school skills that it would allow to count towards its ninety-two-credit curriculum (the ABA standard only requires eighty-three credits for graduation).

15 Members of the working group even sat in on and observed Concord Law class sessions.

16 Concord’s admitted students typically have a lower academic profile than those admitted to Indiana’s current law schools, and its graduates pass the California Bar at a 50-60% rate.

17 The dormant Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution prohibits states from engaging in economic protectionism by creating regulatory structures that benefit in-state entities at the expense of out-of-state entities. See Nat’l Pork Producers Council v. Ross, 598 U.S. 356, 369–70 (2023).

18 The Court provided the report to Purdue for its response. The working group’s report and Purdue’s response are available on the Indiana Supreme Court’s website. See https://www.in.gov/courts/publications/proposed-rules/march-2023/.

19 Indiana is not a mandatory bar state. The Indiana State Bar Association is a voluntary membership organization with roughly 12,000 of Indiana’s 16,000 active lawyers in its ranks. It does not fulfill the same regulatory function as other state bar organizations. The Indiana State Bar Association’s statement on the Concord proposal is available online. See https://www.in.gov/courts/publications/proposed-rules/march-2023/.

20 The Indianapolis Bar Association’s statement is available online. See https://www.indybar.org/?pg=IndyBarNews&blAction=showEntry&blogEntry=90820.

21 Notre Dame did not comment.

22 A number of Concord graduates, including several in Indiana, also commented. One in particular stuck out: the commenter had taken and passed—on her first attempt—the California bar exam. She was not allowed to take the Indiana bar exam. But she was admitted to the bar of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana, because Local Rule 83-5 of the Southern District requires only that an attorney be “admitted to practice by the United States Supreme Court or the highest court in any state” and be sponsored by a member of the Southern District’s bar. It was an expression of rueful irony that this attorney lived and worked in a geographic area of high need, in a practice area of high need, and she was admitted to practice in Indiana’s federal courts but could not do so in our state courts.

23 ChatGPT commented. It was strongly in favor of the proposal, saying, in part:

[A]llowing Concord Law School graduates to sit for the Indiana bar exam would benefit both aspiring lawyers and underserved communities throughout Indiana. It would broaden access to legal education, address the shortage of lawyers in rural areas, promote diversity and inclusion in the legal profession, and provide more opportunities for aspiring lawyers to pursue their dreams. While some concerns have been raised about this proposal, these can be addressed through appropriate safeguards and regulations. Overall, this proposal represents a positive step forward for the legal profession and the communities it serves.

24 Relatedly, Indiana was also one of only fifteen states that did not allow graduates of foreign law schools, under any circumstances, to sit for its bar exam.

25 The proposed amendment, including the existing rule language, is available on the Indiana Supreme Court’s website at https://www.in.gov/courts/publications/proposed-rules/november-2023/.

26 The Indiana Supreme Court adopted the Uniform Bar Exam in 2021. To ensure Indiana lawyers were still provided a functional grounding in Indiana law, the Court requires all applicants for admission by examination to take a nine-module online course on Indiana law within six months of passing the bar exam. Ind. Admission and Discipline Rule 17(2). The course covers where Indiana law varies from the UBE’s model rules on civil procedure, torts, evidence, criminal law and procedure, probate law, family law, professional responsibility, and also sections on Indiana constitutional law and Indiana-specific practice topics like electronic filing and problem-solving courts.

27 IndyBar was concerned with the significant workload this might put on the Board of Law Examiners and that the graduates might not necessarily then go to rural counties to practice.

28 The reasons were similar to the opposition before, although by this time the ABA was doing greater exploration of accrediting fully online law schools. The schools also suggested several alternative approaches to the attorney shortage—many of these approaches are being reviewed by the Commission on Indiana’s Legal Future not as alternative but as additional pieces to the solution puzzle.

29 Both schools have highly regarded LLM programs.

30 The staff agencies for the state’s prosecutors and public defenders—the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council and Indiana Public Defenders Council—despite representing constituencies as tip-of-the-spear on the attorney shortage as any, were both opposed. Both referenced the ISBA’s opposition to the original Purdue Global proposal and the need for ABA accreditation to ensure quality legal education; both believed non-ABA accredited schools might produce students of lower legal skills than an ABA-accredited school. IPDC, like Indiana Legal Services, also sought more concrete standards for the Board of Law Examiners in determining waiver eligibility. IPAC suggested financial alternatives to improve public service attorney salaries, forgive student loans, or offer scholarships for law students committing to careers in public service. Like the law school’s proposals, these are also being considered by the Commission on Indiana’s Legal Future as additional—not alternative—solutions.

31 The order amending the rule is available on the Indiana Supreme Court’s website. https://www.in.gov/courts/files/order-rules-2024-0701-admin.pdf.

32 It’s not clear how many individuals might seek these waivers, but interest in the process has been high. When looking at the original Purdue Global proposal, we estimated perhaps twenty individuals might avail themselves of that process. A small number, to be sure. But in the many Hoosier counties, just one or two new lawyers might make a huge impact.