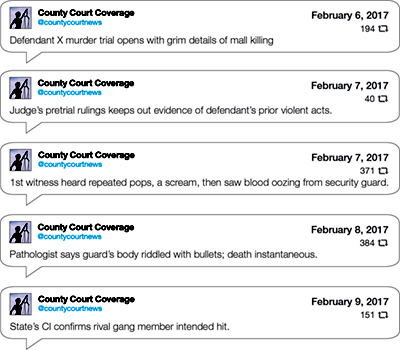

Described by some as “Haiku journalism,” the 140-character limit of Twitter messages such as the fictional examples below, may seem to provide only short-script descriptions of legal events, but these abbreviated statements are beginning to impact court systems.

As reporters and onlookers can give play-by-play-accounts of what is occurring in the courtroom and even include photos or videos on Twitter, courts are wrestling with legal issues regarding this new medium.

Is it broadcasting? Can or should all electronic devices be banned from the courtroom? If not, what, if any, limits are there on the use of Twitter and other means of electronic messaging in the courtroom? In Advisory Opinion #1-17, the Indiana Commission on Judicial Qualifications provides new guidance for judges facing these issues.

Is Tweeting Broadcasting?

Is Tweeting Broadcasting?

The tension between the public’s desire for transparency and immediate information about court proceedings and the judiciary’s obligation to preserve fairness for all courtroom participants and to maintain order and decorum has been a balancing act which has perplexed courts for nearly a century.

In Indiana, that balance is nested in Rule 2.17 of the Code of Judicial Conduct, which prohibits the broadcast of court proceedings, except in limited circumstances. The first question facing courts is whether Twitter use constitutes “broadcasting.”

Nationally, courts that have addressed the issue have reached varied results. Relying on traditional dictionary definitions for the term “broadcast,” courts banning Twitter use in the courtroom found that it constituted broadcasting because it has the ability to make information “widely known” and allows onlookers “to provide up to the minute details of any action or occurrence.” These courts also pointed to the fact that the media regularly uses this medium to report on the news.

In contrast, a Connecticut trial judge in the unpublished opinion of State v. Komisarjevsky, 2011 WL 1032111 (Conn. Sup. Ct., Feb. 22, 2011) looked to the policy considerations supporting the ban on broadcasting in sexual abuse trials and determined that it reaches too far to extend the broadcasting ban to Twitter use. That judge reasoned that, while it makes sense to spare a victim the indignity of having his or her ordeal transmitted to the world with use of actual voices and photos or televised images from the courtroom, the policy consideration supporting a broadcasting ban simply cannot be extended to descriptions of the actual words spoken in the courtroom.

In Advisory Opinion #1-17, the Indiana Commission on Judicial Qualifications agreed with the Connecticut judge’s analysis, recognizing that “transmitting a person’s actual voice and image is qualitatively different, in terms of privacy, security, and reputation, than another person’s report of a witness’ testimony and mannerisms.” The Commission’s opinion, therefore, is that “use of Twitter and similar communication mediums or avenues is not broadcasting under Rule 2.17, unless the message contains video or audio of trial court proceedings or a link to videotaped testimony.”

Can a judge ethically ban electronics from the courtroom or place restrictions on use of electronics in the courtroom?

Although the Commission determined that most courtroom Twitter use does not constitute broadcasting under Rule 2.17, the Commission also recognized that there are situations in which a trial judge may ethically impose reasonable restrictions on use of Twitter (and similar mediums) in the courtroom. The Commission left it to other entities to provide specific guidance on what might constitute a reasonable restriction, but, in the meantime, the Commission’s comments in the Advisory Opinion provide some insight to trial court judges as to questions to ask when deciding whether to impose restrictions on Twitter use in the courtroom.

Questions for a trial judge to consider might include:

- Is the restriction necessary to maintain order and decorum in the courtroom? (i.e. will use of electronic devices be distracting to fact finder?)

- Is the restriction necessary to ensure a fair trial for litigants? (i.e. Are there concerns that a separation-of-witnesses order will be violated or that immediate release of certain information may taint the juror pool?)

- Are there any security interests specific to the trial which might necessitate restrictions on how Twitter is used in the courtroom?

- Will an advisement to the courtroom audience not to record courtroom proceedings and not to photograph any witness be sufficient to prevent improper broadcasting from electronic devices?

- Have there been any instances of abuse of electronic media by one of the parties or someone associated with one of the parties in that particular case or generally?

In many instances, after asking these questions, a trial court judge may be able to reach an acceptable compromise which accommodates both the media’s and public’s interest in transparency while also preserving the litigants’ right to procedural fairness.

As trial court judges face these issues for particular trials, I encourage them to contact the author and to contact Kathryn Dolan, Public Information Officer for the Indiana Supreme Court, at (317) 234-4722.