The Issue

Unless they are there for a wedding or an adoption, people rarely come to court for a happy, positive reason. Judges who handle criminal cases involving allegations of spousal or child abuse, sexual assault, or other violent crimes can count on seeing people who have experienced at least one traumatic event in their lifetimes.

But what about judges in drug courts, veterans’ courts, problem-solving courts, or juvenile courts? Indeed, a party to almost any case type—bankruptcy, eviction, domestic relations, malpractice, or collections—could be dealing with the effects of trauma.

When plaintiffs and defendants come to court, wounds from their past can come along with them, manifesting as behaviors that may frustrate judges and lawyers who are not familiar with the dynamics of trauma—who are not, in other words, trauma-informed.

For example, a defendant might appear “spaced out” or distracted—or might shut down completely—while he is being questioned by a judge. This person’s behavior could actually be a form of dissociation, a protective strategy to help cope with the overwhelming stress of the court appearance. Or a witness might add details while testifying that she never mentioned in her earlier statements to police or counsel, claiming to have just remembered them.

Special Considerations for Children:

With the help of judges, lawyers, and behavioral health professionals, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network and the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges have developed a “Bench Card for the Trauma-Informed Judge.”

Whether the case at bar involves custody, parenting time, detention, waivers to adult court, residential or community-based treatment, children in need of services, or termination of parental rights, judges must account for the effects of trauma on the child.

To access the bench card, along with a fact sheet on helping traumatized children, a technical assistance bulletin listing “Ten Things Every Juvenile Court Judge Should Know About Trauma and Delinquency,” and other resources for judges, visithttp://nctsn.org/resources/topics/juvenile-justice-system

This type of fractured recall, according to experts on the neurobiology of trauma such as Dr. Rebecca Campbell at Michigan State University, is in fact a normal manifestation of how the brain’s memory centers deal with traumatic events.

Finally, a tenant in an eviction case might appear in court while clearly intoxicated—self-defeating behavior, to be sure, but also perhaps a means of self-medicating to avoid the terror of his family’s impending homelessness.

Experts at the National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma, & Mental Health note that when confronted with behavior that seems problematic, a trauma-informed professional will approach the situation not by asking, “What is wrong with you?” but rather, “What happened to you?”

When lawyers, probation officers, court staff, and judges know how to recognize behaviors associated with trauma, they can respond more appropriately and thus avoid compounding the damage that has already been done. Problem-solving courts often offer great models in this respect.

What Judges Can Do

At least one state, Hawaii, offered training in 2013 and 2014 to all of its family court judges to help them better understand how trauma affects the people they see before them in court every day.

Hawaii also offered training on how trauma vicariously affects judges and court staff, because vicarious traumatization is real: a study published in the Journal of Traumatic Stress in 2012 found that even 911 dispatchers experienced acute trauma from handling emergency calls, including calls for domestic violence—some even developed Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome (PTSD).

Anyone who wishes to obtain more information on this topic is encouraged to visit:

National Center on Domestic Violence, Trauma, & Mental Health’s Trauma-Informed Legal Advocacy Project

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration website

The National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges’ website

As an outgrowth of their training on these matters, the Hawaiian judges resolved to require that all court-ordered domestic violence services for victims, defendants, and children employ a trauma-informed approach. They also adopted a mission statement for their family courts that emphasized healing for children and families.

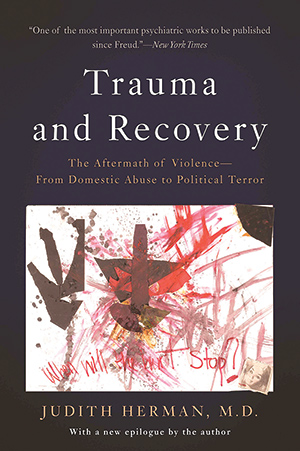

Judges can educate themselves about these issues by visiting such websites as Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration page on trauma and violence and by viewing the materials at the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges’ victim series website. Also, Dr. Judith Herman’s book, Trauma and Recovery, is a must-read for anyone interested in this subject.

Dr. Herman discusses trauma related to war, violent crime, family violence, and imprisonment, as well as promising treatment modalities. And finally, judges can follow the example of Hawaii’s judiciary and demand that providers of court-ordered services demonstrate competence in delivering trauma-informed care to all individuals.